I am about to walk away from two students in need. I am about to turn a blind eye to their needs because of my own frustrations about their situation. I need a reprieve from the constant strain and effort. For months I’ve watched and worked with these students as they’ve struggled to raise a grade in one class while another grade drops, as they’ve become frustrated over failed efforts and given up, as they’ve fought with anger and determination against school policies put in place to help them.

Before this, I would not have tagged myself as someone concerned about social justice—you won’t find it on my 140 character Twitter bio. But as this experience wore on I became greatly concerned about the welfare of these students and the failures of “the system.” The impact that these measures had on my students changed my teaching to emphasize student voice and autonomy while changing how I view the systems we impose on students in the name of helping them.

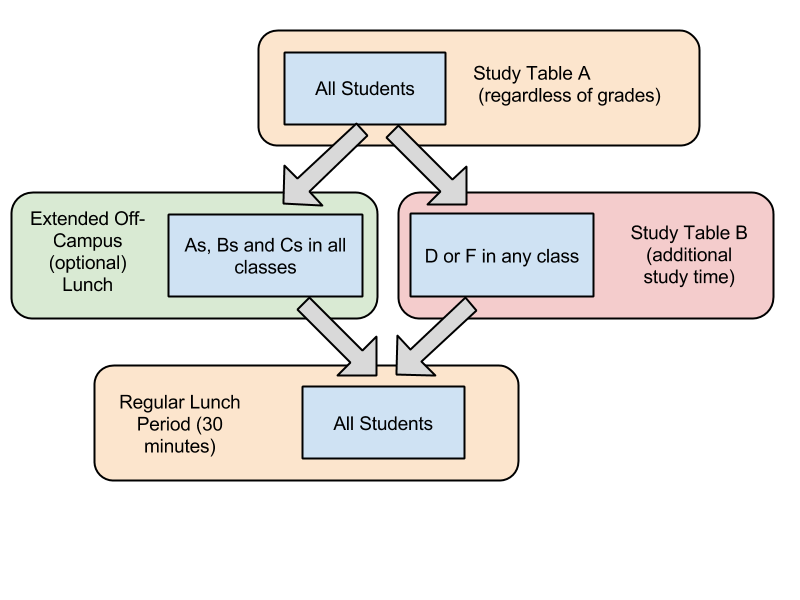

During my first year teaching at a small rural school in Wyoming, the district began implementing an intervention locally known as Study Tables. The intervention was designed by school and district administrators not only to motivate students to maintain higher grades through rewards, but also to provide additional subject specific support, during the school day, to students who were struggling. All students attended Study Table A for 45 minutes to complete coursework. Following Study Table A, students on the “Warning List”—having a D or F in any class—were required to spend an additional 30 minutes on coursework from these classes. During Study Table B, students were sent to receive direct assistance from the teachers of these courses. Students with no Ds or Fs were rewarded with 30 minutes of extra off-campus lunch time.

I implemented the system as its designers intended. Throughout Study Tables A and B, I focused on the students with Ds and Fs. I ensured they were working on appropriate work, helped them in all areas I could, and connected them with their original instructors during Study Table B. I was genuinely concerned for their success. Like other teachers and administrators in my school, I saw immediate success with Study Tables. The students who had always done well continued to do so, and they were now receiving a reward for their commitment to school. Many students who historically struggled academically received additional support and one-on-one time with instructors. As a building, we greatly reduced the number of failing students compared to previous years. The Study Tables system was having its intended positive effect on many of our students.

Even though I saw all of these successes, I was still troubled by some things about Study Tables. There was a grumbling that couldn’t be settled. There were students who detested Study Tables and consistently complained about them, even those who would readily admit that it was improving their grades. In my own Study Tables class, I had two students the system and I couldn’t reach: Jessica and Brandon.

Jessica and Brandon shared a similar experience in my Study Table class. They both started the year like all students: they had no Ds or Fs and hadn’t experienced any interventions of the system. As the year progressed, they both received marks that put them on the Warning List. Most students attending Study Table B were there for a week or two, raised their grades, and never returned. Jessica and Brandon were regulars. Despite the system and my best efforts, Jessica and Brandon still had Ds and Fs in multiple classes—no potential reward or current punishment seemed enough.

Jessica and Brandon went through multiple iterations of a shared cycle, where I both cheered them on and pitied them. They both were their own individuals but also seemed to follow a similar cycle—at times even feeding off of each other’s reactions. At times, one would rise from a moment of despair, gather their determination and honestly attempt to improve their grades. Often, they would raise one or two grades above the threshold only to have other grades fall below a C. Each would then go through stages where they regularly suffered through their daily 75 minutes of Study Tables. Despite at times being at disparate ends of the cycle, they both passed through its different stages. They would cycle between refusing to work, cursing teachers and the school, delight over completing assignments and raising their grades above the threshold, swearing they would never use anything they were being forced to learn, begging to go to lunch with their friends, and looking scathingly at other students who didn’t have to stay behind in Study Table B. I even, sacrilegiously, began thinking of each of them as my “Study Table purgatory students”—students struggling to make their way out of a potentially temporary place through suffering and punishment.

I was as frustrated as they were; at times I even questioned “what is the point?” or “are Brandon and Jessica even capable of this?” I am ashamed to say that I even would go through bouts of giving up on them for a few days or even weeks. I would let them wallow in their self-pity with no outside encouragement and not question the days they would say they “had nothing to work on” when that was obviously not true. As a teacher tasked with implementing this system, I also felt restricted and confined. I felt no control over the situation. I simply followed the directions I was given. This was not the teaching environment I envisioned nor wanted to be responsible for. I always try to instill optimism in my students by embodying it myself, but I also fell into my own cycle of Study Table purgatory.

The plight of Brandon and Jessica was a rough point for me—how could a system that had been set up to help students hurt some so much? This grinding question led me to look deeper into their situation to try to understand their experience, to question my assumptions about the system, its intent, and the results. Why was their experience different from other students? How had I influenced their experience? Their situation also prompted me to collect data through school-wide student and staff surveys on the impact and experiences with Study Tables. These surveys supported both the success of Study Tables and some potential underlying issues. Many students stated that Study Tables was beneficial: “The time is just useful and knowing you have extra time takes off a lot of stress.” Other students expressed the benefit for themselves: “When you are an athlete you spend most of your time at school to begin with and we rarely have time to complete homework at home and get sufficient sleep so, therefore, I love Study Tables.” Still others used the time to reach out to teachers: “I also like being able to go see teachers during Study Table B and to have a long enough lunch to eat and relax before taking more hard core classes.”

Other students and teachers expressed agitation and frustration. One teacher stated, “It’s a waste of time. Study Table B is basically a detention in my mind in which you force kids to stay. If kids want to get their work done they will, forcing them to stay later during lunch just makes them mad and is not productive.” According to another teacher, “Learning to manage time and priorities in high school is essential to being successful post high school. I am concerned that Study Tables forces rather than teaches.” Commenting on the value of Study Tables for all students one teacher expressed that “Study Tables only benefit those who use them properly. Consequently, good students benefit a lot from Study Tables. Apathetic students realize almost no benefit from Study Tables.”

I systematically observed Jessica and Brandon and reflected on their situation and my interactions with them. In addition, I worked with KSTF’s Practitioner Inquiry for the Next Generation (PING) project: a group of educators from across the country who were also raising questions about how to support struggling students in their own contexts. Through this collaborative effort, I analyzed my interactions with Brandon and Jessica and the internal conflict these interactions caused in order to deeply reflect on what it meant for me and my students.

I found myself weighing the benefits I saw from the Study Tables system—the significant number of students who maintained higher grades (and theoretically increased learning) throughout the course of the year against the negatives of the system for students like Jessica and Brandon who were experiencing school as a place of confinement and punishment. I asked myself questions like: Is this what school should be like? Is this anything like the fabled “real world” we supposedly are preparing students for? Are districts and teachers institutionally aware of students like Jessica and Brandon who continue to fall through the cracks? These are the kinds of questions that don’t have easy answers, or answers at all.

Through this inquiry, where I employed multiple methods of observation and reflection that have been explained above, I found the Study Tables system had one of three effects on students: some performed equivalently to how they would have without it; some were helped by the system; and some, like Jessica and Brandon, were hurt by the system. I saw a few key factors that played a major role in Jessica and Brandon’s inability to benefit from a system honestly designed to help them. These factors are choice, voice, and autonomy.

As students progress through school, they are allowed fewer opportunities for choice and must learn to “figure out” what others want them to do—they must become accustomed to complying with an external system. Students in Study Table B experienced a removal of choice that was open to their peers; some students had an extended lunch while others had forced study time. This formed a clear separation and a clear “moral of the story” for students: the “smart” kids get rewarded and the “dumb” kids get punished.

This was not the teaching environment I envisioned nor wanted to be responsible for. I always try to instill optimism in my students by embodying it myself, but I also fell into my own cycle of Study Table purgatory.

Through this experience I can now see that many of the things we do in school have a similar impact on students as Study Tables did on Brandon and Jessica. There are bells that tell you where to go and when to go there, rules and obligations that differ classroom to classroom, and adults who regulate whether you get a drink or use the restroom; these are very basic and simple choices that nearly every person in the world has command over, but often not students. In many ways we are preparing them for a “real world” that doesn’t exist. This is one of the unfortunate “stories of the world” we inadvertently, but very clearly, teach students in a system of education that continually removes their choice, voice, and autonomy.

It was a moment of realization when both of my students, Brandon and Jessica, left the normal school system mid-year for environments they saw as affording more choice and autonomy. Both moved to alternative learning environments, although they took different paths. Jessica dropped out of our school and enrolled in an online school. I don’t know if she ever received a diploma. Brandon got a GED and takes intermittent courses at a local community college; however, he has few concrete plans for his future.

The experience with Brandon and Jessica deeply changed my attitudes towards and goals for teaching and learning. Their experience and my involvement in perpetuating it has developed into a multi-year quest to recreate my classroom environment. I am exploring what happens when I release ultimate control and provide more choice, voice, and autonomy in learning to my students. Through an enduring effort to continually refine, reflect and improve, my students have much more individual control and involvement in their learning.

I have come to understand that an active learning environment isn’t just about having students actively engage in an activity but instead requires student agency in what they are doing. This agency (or choice, voice, and autonomy) may include the topic, the time, or the product. I still help guide the end result of the learning, but how students learn is more open than ever before. I have found that providing this change is as simple as having multiple versions of a task and letting individuals or groups of students select the version they would prefer (i.e., reading assignment vs. video vs. diagrams vs. direct instruction from me). I have changed my class so that student teams select what assignments they will complete each day—they know their goal, their requirements and their learning targets—and they are trusted to be responsible.

Through this change, I have witnessed students developing and practicing skills that will allow them to be critical thinkers and problem solvers. Because of the learning environment I have created, my students have more ownership of their learning and are better able to discuss and debate their understanding and apply it to situations outside of our classroom. For example, students in my environmental science course recently defended recommendations for a deer management plan before our Town Council, which is struggling to cope with various issues surrounding an overpopulation of deer. I have found that giving students some control over their classroom experience makes it more likely they will choose learning over anything else.

The experience with Brandon and Jessica deeply changed my attitudes towards and goals for teaching and learning. Their experience and my involvement in perpetuating it has developed into a multi-year quest to recreate my classroom environment.

These changes have also dramatically changed my role as a teacher: I am no longer the ultimate planner and owner/disseminator of the content for my students. I now serve as a facilitator in their learning and growth. I used to direct what students did each day: which assignment, which reading, and when they should be finished. Now I provide students all of the expected assignments for a unit (including options between various formats on some), the final expectations and goals, a final due date, and a few check-in points along the way.

This simple process has put much of the power in my classroom back in student hands. I regularly see students exercising autonomy in collaborating together to prioritize their time and focus on areas that they need the most help with—something that good teachers always try to do for their students. I see students exercising personal choice by deciding to work on team assignments during class while they assign each other reading assignments as homework. I see students prioritizing their class time so they can receive feedback on their work from me. Teams exercise their voice by setting their own deadlines to hold each other accountable. As a result, I spend less time monitoring and enforcing deadlines. Instead, I am focused on student understanding. I am a much more fulfilled teacher.

The most critical personal growth to emerge from this inquiry into two students in my classroom has been my own, resulting in a fundamental change in the teaching and learning experience for all students in my classes. This came from the deep and critical inquiry into the experience of two students in my class. By observing and deeply reflecting on the personal interactions that take place each day, a teacher can glean the evidence needed to shift and evolve their classroom instruction to provide more complete and meaningful learning and develop the skills and attributes of lifelong learners in students.

¹Names changed

London Jenks is a Knowles Senior Fellow. He teaches physics, earth science, and environmental science at Hot Springs County High School in Thermopolis, Wyoming, where he also supports teachers and students as the District Technology Director. London was a member of the KSTF teacher inquiry group, PING (Practitioner Inquiry for the Next Generation), for three years. London is currently in his sixth year of teaching and working on a master’s degree in education leadership. London can be reached at london.jenks@knowlesteachers.org.